Every time I do an interview (which, I must admit, has not been many times), someone asks me: what did you learn about the 1950s while writing this series? The answers are too numerous to really list, so I usually just say that the American mid-century was a lot worse to live in than people can either admit or understand. It was horrible. Really.

But I have learned quite a bit, and fallen down a few rabbit-holes of information I’d love to share with you. And one of them was learning about queer rights groups that emerged far, far earlier than media would like you to know.

The first book of The Girl Friday Mysteries only slightly touches upon the burdens of being LGBTQ+ in conservative, mid-century America, but I did a lot of research on the full extent of the persecution of queer people because I just… needed to know. And while doing so, I stumbled upon a group I’d never heard of before: The Daughters of Bilitis (bill-E-tus).

The Songs of Bilitis

In 1894, a Belgian-born, French writer named Pierre Louÿs published a book of poems called The Songs of Bilitis, claiming to have found a series of poems in Ancient Greek on the walls of a tomb holding the body of a courtesan named Bilitis. The courtesan was similar to, and a contemporary “friend” of, the well-known and celebrated poet Sappho. (You can learn more about Sappho from my favorite mythology podcast, Let’s Talk About Myths, Baby!)

Raised in an entirely female society and textually showing a reticence if not fear of men, Bilitis reads as super, duper gay.

The book was a pseudotranslation that, at the time, fooled even scholars. Louÿs wrote every poem himself, and even created a fictional biography– discovered during a fictional archaeological dig– in order to construct a narrative of a “lost manuscript” around the publication of some reasonably racy poems. He was a friend and contemporary of Oscar Wilde, and gay rights activist André Gide. (Louÿs himself was married to a woman and had two children, though as we know that is not evidence against queerness.)

The dedication of the book is inscribed “This Little Book of Antique Love is Respectfully Dedicated to the Young Ladies of the Society of the Future.”

And the Young Ladies of the Society of the Future found Bilitis.

The Daughters of Bilitis

The Daughters of Bilitis were the first lesbian rights group ever founded in the United States, in the year 1955– so just a few years after the events of Viviana Valentine Gets Her Man, which takes place in 1950.

Founded by Rose Bamberger and her partner Rosemary Sliepen as “a social club for gay girls,” they were joined by Del Martin and her partner, Phyllis Lyon, Marcia Foster and her partner June, and Noni Frey and her partner Mary. Last names for some of the founders have been lost to time, but it is known that Rose Bamberger was Filipina and it is believed that Mary was Chicana, so it is vital to note that the activist group was at least nominally diverse at the outset.

They named the group after a fictional lover of Sappho for obvious reasons. An article by Ashawnta Jackson on JSTOR Daily sums it up perfectly: “For those who knew, the name was beacon; for those who didn’t, it was just another women’s club.”

At the time, police raids on gay bars were both frequent and violent, and Rose suggested that she and her lesbian friends meet at her home, in order to avoid police persecution. Within six months, several members of the original social club moved to turn the group into an organization more focused on social justice and action. In a result familiar to many of us, Rose and Rosemary left the group leadership, as they were more working class than the other couples and feared the impact of reprisal on their more economically tenuous positions within San Francisco. While they remained on the mailing list for the DOB’s newsletter, The Ladder, Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon are generally considered to be the leaders of DOB after 1955.

By 1960, the group had chapters across the country, in Rhode Island, New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles.

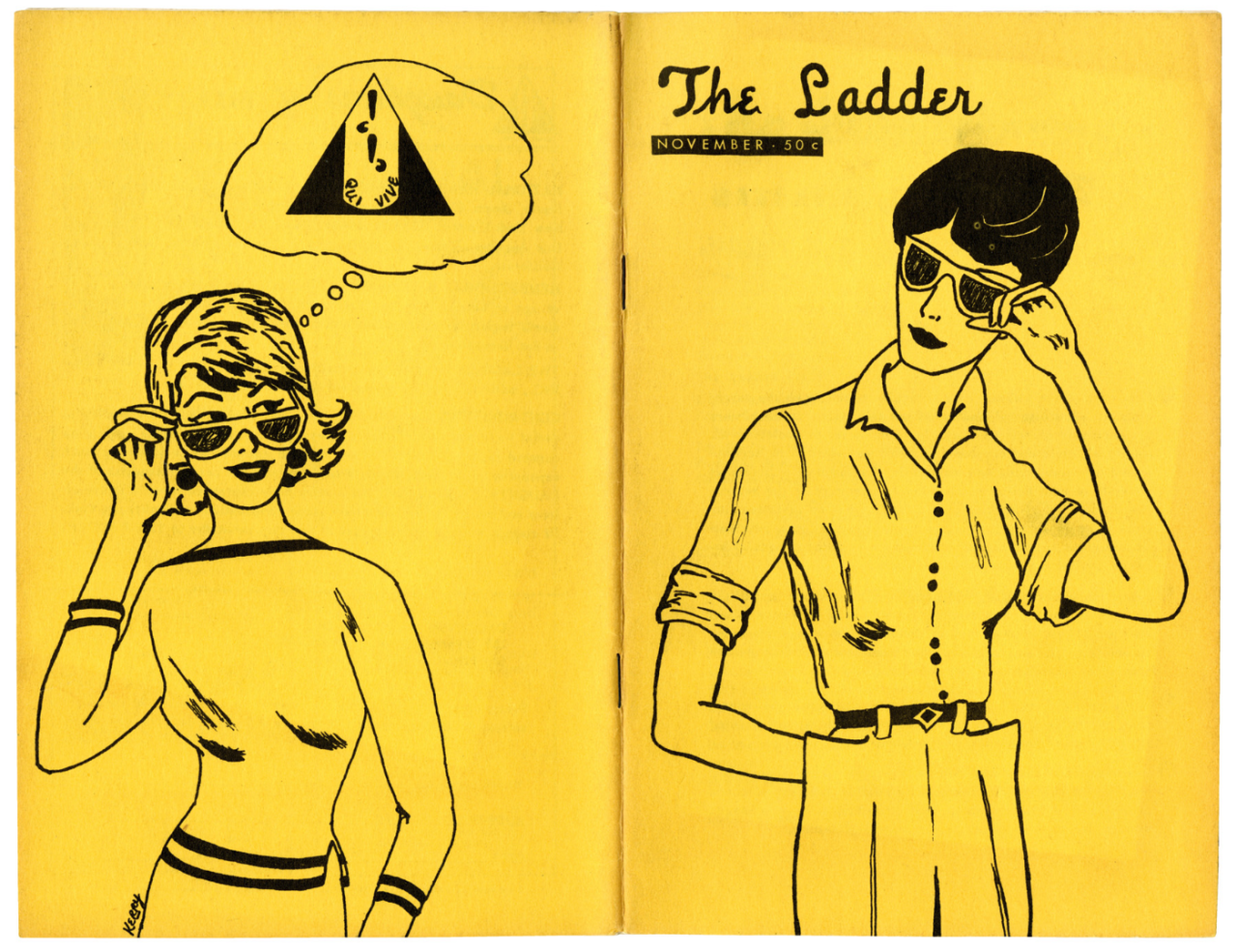

The Ladder

While other lesbian newsletters and publications existed prior to The Ladder, the DOB’s magazine is credited as the first nationally published and distributed print for lesbians in the United States, premiering in 1956 and published until 1972.

As early as 1965, Eckstein and other members of the group were coordinating travel to national pickets for LGBTQ rights in Philadelphia and Washington, D.C, publicly outing themselves both as queer and as activists. It was a dangerous time to be either.

Additionally dangerous was the existence of what one obviously needs in order to distribute a newsletter: that is to say, a database of subscribers. Each of them, a politically active, gay woman. The DOB frequently had to assure subscribers that they took serious precaution with their mailing list, and that they would not share information with anyone willingly, writing, “Your name is safe.” However, subscribers did have a right to be nervous– founders of the DOB and editors on The Ladder were watched by both the CIA and FBI.

One of the publications earliest subscribers? Lorraine Hansberry, the author of A Raisin in the Sun, was the first Black American female author to have a play performed on Broadway. Living for many years as a closeted lesbian in a straight marriage, during her first separation from her husband, Robert Nemiroff, she wrote to The Ladder under the name L.H.N. and said, “I’m glad as heck you exist.”

It took until 1963 before a photograph of a real woman graced the cover of the magazine; prior to that, it had been drawings of women. In 1966, a portrait of lesbian activist Lilli Vincenz was the first image to appear on the cover without the model’s face obscured by sunglasses, or in profile to hide her full identity.

Politics

At the outset of the group, Martin and Lyon pushed for assimilation as much as possible, urging feminine dress and other actions to make the straights more “comfortable” with lesbians in society– though tactically, the urge for feminine dress also precluded activists from being arrested for cross-dressing, which was the punishable crime. Laws against homosexuality at the time focused exclusively on cis-male people/gay men. The overall politics of the DOB were at the time and are today criticized as being conservative and focused predominantly on white, upper-middle-class, and upwardly mobile educated women, though the audience was more varied– likely due to the fact that other options for print publications were limited.

Throughout the group’s and publication’s existence, leadership waffled between this conservative mode and occasionally into more overt activism. Towards the end of The Ladder’s publication, its editor, Barbara Grier, removed the word “lesbian” that was then on the cover and the content was adjusted to be more amenable to generalized feminists. The publication, under Grier’s guidance, lasted only another four years.

Legacy

There is an incredible trove of information on the Daughters of Bilitis on the internet, and I urge you to sit down and read more on the history and evolution of the group. It has opened my eyes to just how slow the fight for rights and recognition has been, and further underscored just how tenuous LGBTQ rights remain.

If you’d like to offer further sources of information on the DOB or other LGBTQ rights groups, please do leave a comment below. I would love to know, and share with other readers!

Updates:

After my previous newsletter, my friend, Dr. Bethany Brookshire, wrote to tell me the thing about bats is entirely untrue and that there is so much variation in the teeth and mouth structures of bats throughout the world that you do not have to worry about being bitten by one unless you were, you know, really bitten by one. Bethany is the author of the book Pests: How Humans Create Animal Villains and you should buy it.

Leave a comment